Sandakan – Flora and Fauna – Beyonder

Sandakan does not overwhelm you at first glance. It doesn’t announce itself with drama. It looks almost… ordinary. And then you begin paying attention.

Sandakan sits on the east coast of Sabah, edging one of the most biologically dense regions left on Earth. The forests here belong to the great Bornean lowland rainforest system — ancient, layered, stubbornly alive.

This is not curated wilderness. It is wilderness that still believes it owns the place.

An ancient system in Sandakan, not a collection of animals

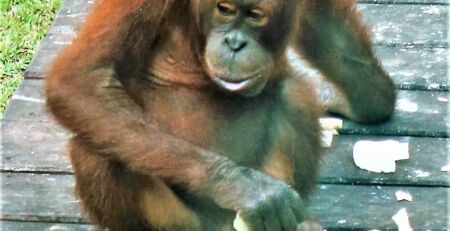

It is tempting — and deeply wrong — to talk about Borneo’s wildlife as a checklist. Orangutan: tick. Elephant: tick. Proboscis monkey: comic relief.

But Sandakan’s forests are not a zoo without fences. They are an ecosystem, and one that evolved over 140 million years. Every species here exists in relation to something else — trees, rivers, insects, fungi, seasons.

The towering dipterocarp trees dominate the canopy, some rising over 60 meters. They do not fruit annually, but synchronize mass flowering events every few years — a strategy so old and successful that modern science is still catching up.

Below them thrive lianas, epiphytes, strangler figs — plants that don’t politely wait their turn, but negotiate aggressively for light and space.

This is a forest that does not believe in fairness. Only in survival.

Sandakan’s Proboscis monkeys and evolutionary audacity

If there is a face of Sandakan, it belongs to the proboscis monkey.

With its oversized nose, pot belly, and permanently bemused expression, it looks like evolution briefly developed a sense of humor. But the nose serves a purpose — amplifying calls, signaling dominance, attracting mates.

They are endemic to Borneo – you will not see them anywhere else.

Watching them along the Kinabatangan River in the early morning or at dusk is a quietly theatrical experience. Families emerge, leap across branches with surprising grace, then settle into riverside trees as evening approaches.

There is something oddly urban about the sight — the way they return home en masse, jostling for space, negotiating hierarchies. It reminded me strongly of Mumbai’s high-rises lighting up at dusk, offices emptying, homes filling, the city reassembling itself.

There is something oddly urban about the sight — the way they return home en masse, jostling for space, negotiating hierarchies. It reminded me strongly of Mumbai’s high-rises lighting up at dusk, offices emptying, homes filling, the city reassembling itself.

Except here, the city is green. And it runs on instinct.

The gentle weight of pygmy elephants

The Bornean pygmy elephant is smaller than its mainland cousins, with rounder faces and a temperament that feels almost apologetic.

Seeing one — if you are lucky — is not dramatic. There is no charging, no spectacle. They appear quietly, often at the river’s edge, moving with an awareness of their own vulnerability.

Their presence is deeply emotional. Not because they are rare — though they are — but because they feel out of place in a world that is shrinking around them.

They remember a forest that was continuous.

Sandakan – The Predators you rarely see (and shouldn’t)

Sandakan’s forests are home to clouded leopards, sun bears, and other apex species that most visitors never encounter.

That is not a failure of tourism. It is a sign of ecological health.

The clouded leopard, in particular, feels almost mythical — arboreal, elusive, beautifully adapted. Its absence is its success.

The forest here has not yet been reorganized entirely for human convenience. That is both its fragility and its power.

Birds, insects, and the unseen majority in Sandakan

Hornbills announce themselves loudly — wingbeats heavy, calls echoing. Kingfishers flash electric blue. Eagles patrol overhead. Reticulated pythons wait patiently.

But the true majority here is smaller: insects, amphibians, fungi. Things that hum, click, glow, and quietly do the real work of the forest.

But the true majority here is smaller: insects, amphibians, fungi. Things that hum, click, glow, and quietly do the real work of the forest.

Sandakan teaches you something important:

Nature is not charismatic by default. It is functional.

Charisma is optional.

This was Part of the Mini Blogs on my travels in Borneo… Read the full travelogue here…

Check out the Borneo packages available for you to choose from. Need something different? Contact Beyonder Travel.

Leave a Reply